Sunday, May 4, 2008

Tracking the Postcards

Writing Postcards in Astor Place

My line: "Would you like to send a postcard to anyone in the world for free" I tired out a variety of opening lines and this was the one that got the most takers. I then went on to explain the project and that if they wanted to write a postcard I would drop it in the mail for them. I think I approached 100 people and got 45 postcards which I feel is pretty good. Of those who wrote cards they thought it was great and not to give myself too much credit, I think I made some peoples days. For those who said no, some were polite, others, well just downright mean. I got quite a few "No, I would NOT like to do that." Polite but also a bit harsh. Most of the postcards are staying in the country but one is going to Taiwan and the other is on its way to Portugal. A lot more people would have written internationally but they didn't know the address of the top of their head. These postcards are another 45 reasons why I love New York and the people who will stop for the clipboard people!

Sunday, April 27, 2008

Astor Place Manifesto

One hundred and fifty nine years ago 22 people were killed and at least 38 were injured on the corner of

In 1847, the Astor Place Opera House (now home to a Starbucks and an upscale residential apartment building) opened to serve as an outlet for wealthy theatergoers who wanted to avoid the immigrant clientele of the East village and the “Five Points” section of lower Manhattan who frequented the Bowery Theater (located at Bowery between Canal and Hester). The new Astor Place Theater, with its high ticket prices and dress code, became a symbol of classism and Anglophila to many working class New Yorkers.

On

Astor Place Riot: NYPL Digital Library

I came across this history while researching Astor Place as the location of my project. I was initially drawn to Astor Place because of its crossroads of streets and neighborhoods that predate Manhattan’s city grid. As road’s criss-cross each other, and traffic, both vehicular and pedestrian converge in a messy battle over who has the right-of-way, Astor Place, to me, has always been a place where one can truly get lost in the city. Geographically and architecturally, Astor Place represents the old and the new and both its 19th century and 21st century architecture have become monuments of the city. Astor Place is famous for its three Starbucks’ and it’s recently finished undulating glass apartment building designed by Charles Gwathmey.

But equally famous is the dingy opening to St. Marks Place, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art established in 1859, and the Astor Place subway station which, completed in 1904, is one of the original twenty-eight stations in the subway system.

Charles Gwathmery’s glass apartment building

Cooper Union

History and identity have always gone hand-in-hand in my mind. As someone unsure of my own identity and history, I am drawn to places rich in history but where identities become muddled and histories collide. My first idea for a final project was to do something in my

Later in his writings Wodiczko refers to specific “communicative instruments” that could be used to both heal the immigrant’s trauma of resettling as well as act as a conduit between the immigrant, “the vanquished,” and the “victor.” This hit a cord with me because this is exactly the thinking I am trying to work out as I teach photography and video to the “vanquished” and subsequently, the “voiceless.” Simply put, how do, and how can, people talk to each other?

As my thinking process continued and I decided on

I thought, what if I gave people the opportunity to write to their past? To remind themselves where they came from in order to think about where they are going. With this question guiding me I began to question more and more the issues of communication: speaking, writing, the Internet, email, letters, postcards, telephones, webcams, and speakerphones. Issues of time, space, and place arose as I questioned the difference between writing and sending an email and writing and sending a letter. One can physically touch a letter, turn it over, feel it, and smell it. It is left with the marks of its travels, stamps, creases, ink smudges. While email is certainly faster by collapsing international time zones and the days it would normally take for a letter to cross the oceans, an email still remains intangible. As we write something it immediately becomes past, this sentence is now history. In an email you can get responses in seconds while in a letter it may take days. The history of a few minutes is far different than the history of a few days. While the Internet collapses time, “snail mail” extends it by allowing the present to be remembered days after.

I wonder how many of us have written a letter or a postcard in the last week, month, or year? With email this method of communication appears to be outdated and yet nothing quite compares to opening your mailbox and seeing a letter or postcard addressed to you. But I don’t mean to evoke a pre-Internet nostalgia, I for one could not say when the last time I used “snail mail;” however, I am interested in both the tangibility of the postcard and the ability for people to write postcards in the middle of the street.

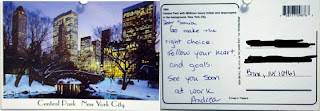

My project consists of present day postcards of

The writer can sign the postcards or they can be anonymous. The anonymity allows for people to share things that they might not share otherwise. As Wodiczko speaks of a communicative device to act between the “victor” and the “vanquished,” a postcard could serve as therapy, to get something out in the open, or simply a way to say hello.

Foucault writes, “We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.”[iii] This resonated with me as we are products of our own pasts as well as the pasts of those around us and the actions of those who came before us and before them. We are products of what happened five minutes ago and what happened five years ago. As the postcards take a few days to reach their destination new history will have happened in that span of time and the postcard will become outdated.

Postcards, unlike sealed letters, are public. Not only will I be able to read the postcards but the post office staff will be able to as well. I can, if I so choose, to share particularly interesting postcards with friends or with the class. People who choose to write a postcard do so knowing that their privacy might not be upheld. Postcards however are still private. They are a letter from one person to another and people can choose to disclose what they want. The streets of New York are both public and private as well. People joke that New Yorkers don’t smile at each other or say hi to one another on the street. People are in their private spaces: headphones on, head down, eyes straight ahead. However, nothing is seemingly more public than the streets of New York. By engaging with my fellow New Yorkers and removing them from the privacy of their own thoughts and actions I am contributing to the democratic nature of New York streets where on any given day and on any given street corner you can be talked to, yelled at, given a leaflet, asked for money, spat upon, laughed at, or ignored.

In this project I am acting as a conduit between people in Astor Place and their pasts as well as their futures. Sometimes in New York it’s easy to get caught up in yourself, your work, and your daily interactions with the city. At most I want to give people the opportunity to take a moment and say hi to someone they haven’t talked to in a while. By tracking the postcards, the project will culminate in an online map of moving history as it travels throughout the world. As Foucault suggests, we don’t live in a void without history. By remembering our own history we are better prepared for the future.